Maty's blog

| 2025-04-04 |

| Busy, busy |

| Okay … I'll admit it. If I didn't bite off more than I can chew, I've at least started the year with quite a mouthful. In part this is due to my being laid low by 'flu last November, and while I was abed the work I should have been doing just kept piling up. However it's also my own fault that I have added a lot of frontlog to go with that backlog, taking on work that I don't really have the time for, but which was too much fun to turn down. As a result I start every day by putting aside mere priority tasks so that the high-priority tasks can be replaced by the ultra-high priority ones. I'm keeping to my deadlines but at the cost of some late nights and turning my social life into a distant memory. (Not that the latter is a major problem - I rather prefer hanging out with Pindar and Livy in any case.) My long-suffering wife insists that in order to prevent me from melding with my computer chair I get out into the mountains at least once a week. Snowshoeing in the high peaks not only gives me a chance for mental refreshment in fantastic scenery but also burns off fat from the peanut pile I keep on hand while working. However, last Wednesday saw me spike my walking poles into the snow for the last time this season. It's not that conditions are too bad right now but wildlife is waking or moving up from the valleys with the spring. There's hungry bears, cougars and packs of coyotes all looking for their next meal – and I'd rather prefer not to be it. Not that all exercise is lost. Today for example I was able to choose between reading the galley proofs for my forthcoming book on the Punic Wars, preparing twelve hundred words on the Oracle of Delphi, roughing out an article on Roman hairstyles, taking a chainsaw to a tree that collapsed under the snow in the back yard, or nailing back parts of a fence that broke when the roof shed a few hundred kilos of snow onto it. It looks like 2025 is going to sort of whizz by. But that's not a problem, because I've promised myself that 2026 will be taken at a much more leisurely pace. For sure. |

| 2025-03-04 |

| Batty Chronological Endeavour (BCE) |

| Call me a curmudgeonly old man. Why not? I'm a pensioner and I certainly get ratty with kids on my lawn. So let me have a bit of a rant here. Specifically about one bit of virtue-signalling that really grates on me - the use of CE and BCE as a dating method. My main complaint is that it is downright wrong. I am assured that CE stands for 'Common Era'. So what exactly is 'common' about it? For a start we appear to have just two, CE and BCE , so we can hardly describe one era as being more common that the other. 'Common' in the sense of shared experience? Well hardly. For ninety percent of the 'common era' few people knew much about people living just a few days travel away, let alone on the other side of the world. In fact given the extensive trading networks of the Romans, ancient Europeans knew more of the world than their medieval counterparts. So if we are going to have a 'common era' I would start it at the earliest in 1492, which leaves three quarters of the era unaccounted for. I suspect that the real reason is because we don't want to impose a Christian dating system on people who do not follow that religion. Which is a bit of a problem since today few follow the Germanic religion which gave us the Moon, the Sun Tiuw, Wotan, Thor, Saturn and Freya as the days of the week. Nor the gods and goddess Janus, Mars and Maia in the first half of the calendar year. Personally I'd recommend keeping BC and AD without attaching meaning to them – just as many people neither know nor care why they use the letters AM and PM for times of day. After all, if modern checks of biblical chronology show that Christ was probably born in 4 BC, then BC doesn't actually mean much anyway. |

| 2025-02-03 |

| Romans in Winter |

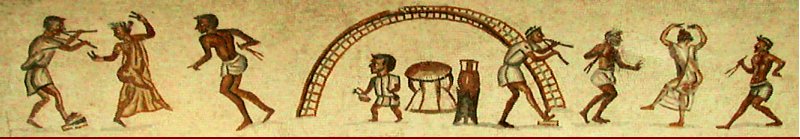

One advantage of country living is that one has a large garden. One disadvantage of country living is that one has to maintain a large garden. When I lived in the UK gardening mostly consisted of picking up the beer cans that local louts had tossed on to our tablecloth-sized patch of lawn. No-one mentioned that later in life I'd be looking piles of bear poop amid acres of dandelions. So I rather like gardening in winter. Outside the Domus Matyszak at present the snow is two meters deep. In places it's up to the roof. The only thing one needs to do is occasionally don snowshoes and chainsaw away tree branches drooping with snowload that are threatening the windows. Otherwise everything slumbers peacefully unattended. It was pleasant then to discover that the Romans also rather enjoyed winter. Apart from those living in the mountains, Italian winters are cold and rainy rather than snowy. Nevertheless, rather as with my garden, there's not a lot to do with growing stuff – which is what most Romans did for a living - so they could spend plenty of time by the tavern fire. If one did have to go out, the Roman's preferred dress was the paenula, a heavy woollen cloak that came with a hood. Of course a toga itself is plenty warm - wrapping oneself in what is basically sixteen square meters of blanket is a good way to keep off the worst of the winter chill. Therefore boots, socks (Roman socks were strips of cloth sewn together rather than the modern knitted tubes) a toga and paenula were protection enough for even the worst of winter's blasts. If it was raining, then a subpaenula might be needed - this was a thinner cloak worn under the heavier one. This was made of unwashed sheep's wool – rich in waterproof lanolin oil – or wool with wax worked into the fibres. Winter was a time for (literally) chilling out and working on personal relationships. In the case of the poet Horace this included romancing a lass called Leuconoe (Odes 1.11) Winter will come on ... While we drink the summer’s wine. See how, in the white winter air, The day, like a rose, droops Toward the outstretched hand Seize it before it's gone. |

| 2025-01-05 |

| Ave MMXXV! |

| Well, the back end of 2024 was certainly not kind to me. That nasty dose of the 'flu hung around all through December, though it faded enough for me to have a pretty good Xmas. Now it's January of a brand new year and I'm horrified by how much of 2024 remains for me to clear up. Even though I was working when I could there was time spent on doctors visits and the hospital, not to mention days when I was basically out for the count. So now there is a book proposal that needs to be in next week, the picture suggestions for a MS I have just completed, the texts on Augustus that should have been there before the new year, and several more odds and ends that should have been wrapped up by now. It's amazing how far one can get behind in a month. On the other hand, recovery is now well under way - I even went snowshoeing last week (though don't tell that to any of my impatient editors). However, all this has definitely reminded me what my new year's resolution has to be. *Slow down*. Last January I decided that as a pensioner I should spend more time with lakes and mountains and less time at the computer. Looking at my schedule for 2025 I can tell you that i failed. However, 2026 will definitely definitely the year I start turning down new projects and taking it easy. Absolutely. For sure. |

| 2024-12-04 |

| Plague Victim |

| Towards the end of the fifth century BC the doctor Hippocrates noted a new kind of fever. This he called the 'cough of Perithous' and noted that the accompanying fever was short-lived and generally not fatal though it did debilitate its victims. The illness, noted Hippocrates, was highly contagious and dangerous to the elderly or those with an underlying health condition. It would take another thousand years for this illness to be called 'influenza'. Italians of the Renaissance noted that the disease was particularly virulent in the autumn and reckoned this was due to the 'influence' of the stars. Today those looking for a few extra days off work might pass off a bad cold as 'the 'flu'. It's not the same. A cold leaves its victim feeling miserable for a week – influenza knocks you flat. I'm particularly bitter about the dose of influenza from which I'm still recovering, because I contracted it when going into town for a covid vaccination. All the symptoms described by Hippocrates are still there – fever, check. Exhaustion, check, and cough, yes, curse it, that cough. The one that keeps me (and my long-suffering wife) awake at nights and has caused the doc to stuff me full of pills because it looks like mutating to pneumonia. (Well spotted there again, Hippocrates.) 'Feelings of tiredness may last ten days longer than other symptoms' the health Canada website informs me. This has led to some anxious emails from editors concerned about my health, (especially as this pertains to pre-Xmas deadlines). Fortunately Ancient History is my happy place, and rather than laying off the history I'm spending even more time in the past as I struggle to forget my illness-wracked present. Hopefully I'll be well for Christmas and ready to go roaring into 2025. |

page 1 page 2 page 3 page 4 page 5 page 6 page 7 page 8 page 9 page 10 page 11 page 12 page 13 page 14 page 15 page 16 page 17 page 18 page 19 page 20 page 21 page 22 page 23 page 24 page 25 page 26 page 27 page 28 page 29 page 30 page 31 page 32 page 33 page 34 page 35 page 36 page 37 page 38 page 39 page 40 page 41 page 42 page 43 page 44