Maty's blog

| 2018-04-05 |

| The Rites of Spring |

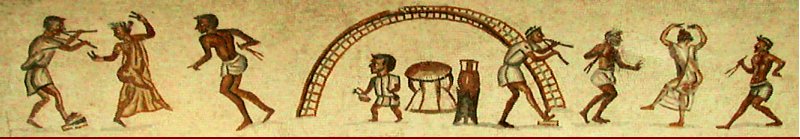

| Last week Easter Sunday and April Fool's day were one and the same. (Memorably celebrated this year by a relative who arranged the usual Easter egg hunt for her kiddies, but didn't hide any eggs. I consider this a valuable life lesson for the young 'uns.) Anyway, the conjunction of dates led someone to ask me whether the Romans had either April Fool's day or Easter. Easter has certainly a long tradition, because spring festivals are ubiquitous in northern cultures. In fact some medieval writers claim the name of the Christian holiday comes from Eastre, a Germanic vernal Goddess. Her symbol was the hare, which is why we have the Easter bunny. In ancient Rome there was Attis the lover of the goddess Cybele who was considered reborn with the spring, and also Mithras, whose birth was celebrated on the winter solstice and his rising from the dead celebrated on the spring equinox. The traditional hot cross bun also has a history. Apparently the church originally tried to ban the pagan rite of baking sweet buns to welcome the spring - a tradition which goes back at least to Roman times. Eventually the clergy gave up the attempt, but the cross was added to show that these were good Christian buns, not some pagan culinary atrocity. Practical jokes were certainly a Roman tradition, but not celebrated particularly on April the first. There is for example the 'Tantalus Cup' - a surviving example of what is also called a 'greedy' or 'Pythagoras' cup. If he pours in a modest amount of wine, the drinker is fine. However, a hidden siphon ensures that if filled past a certain point, the cup leaks all its wine over the drinker's lap. (You can still buy modern examples of these cups online.) The emperor Commodus was an extreme practical joker. We are told of guests who awakened after a drunken party to find that they were sharing their bed with a lion or tiger. The animals were tame and allegedly harmless, so the only casualties were those guests who died of fright - which of course made the whole prank all the more hilarious. |

| 2018-03-04 |

| The (witch)doctor will see you now |

| Recently I was discussing ancient medicine with a friend. That friend is a medic himself, and was somewhat appalled by one of the remedies suggested by the elder Pliny. This was that nine pellets of hare dung taken daily prevents saggy breasts. I then pointed to another recipe that probably seemed no more or less bizarre to Pliny. This said that when willow bark is pounded into paste, that paste can be eaten for relief from rheumatism. Ah, said the friend, that makes perfect sense because willow bark contains salicin, which is the basic ingredient of aspirin. However, my point was that Pliny didn't know how basic molecules act with the body's T-cells, or anything about the major histocompatibility complex. He had to go with what people told him, and as any doctor will agree, that's a tough way to practice medicine. Consider the pellets of hare dung. You'll probably agree that someone who is that desperate to maintain a particular body image will also do the other things - such as diet and exercise - that are actually effective. This makes it harder to separate what works from what does not. To make it even tougher, there's also the well-known 'placebo effect' which means that some potions work because people believe they work. Someone suffering from insomnia who starts wearing an amulet that prevents sleeplessness might well sleep like a baby afterwards, simply because he believes the amulet will work. Is the amulet therefore effective? 'Magical cures' and 'real medicine' co-existed in the ancient world. A physician might clean a wound and wrap it in a clean bandage before adding a magical sigil to the dressing to speed recovery. Hippocrates (an ancient doctor himself) said the first law of medicine was 'do no harm'. Unlike hare dung pellets, most magical conjurations did no harm and might do some good. The rest was informed guesswork. After all, even in these days and despite our much greater understanding of how the human body works, a considerable percentage of the population prefers to use alternative medicine that we might say is well, very alternative. |

| 2018-02-04 |

| Strong feelings about Sparta |

| Well, 'Sparta: Rise of a Warrior Nation' has been out for several months now, and I'm getting interesting feedback. That is to say, a some people have written to me complaining that I have portrayed a bunch of psychopathic killers too sympathetically. These correspondents point to Sparta's brutal child-rearing practices, the savage oppression of the helots and the nation's glorification of war. It is beyond my correspondents how I can excuse or gloss over such behaviour, and my doing so is a cause of some disappointment. On the other hand, there's a viewpoint most strongly expressed by the gentleman who wrote to accuse me of being a touchy-feely liberal (I'm pretty sure that 'liberal' was meant as an insult here), who has unfairly maligned a proud race of noble warriors. How would I feel at Thermopylae if I had to fight alongside a bunch of tree-huggers and Bolsheviks? Actually, while I can't speak for the tree-huggers, I believe the Bolsheviks were rather mean fighters. However, that's not the point. What is interesting is that that Sparta raises such strong feelings even today. No-one gets anywhere near as partisan about - for example - the Thebans. This has caused me to wonder why. I think that many people have their own personal Sparta. Admire or loathe the Spartans, but this now extinct people identify well with certain qualities. Call a room 'Spartan' and you immediately get an idea of the furnishings. Call a meal 'Spartan', and you start to yearn for chocolate bars. If for you personally Sparta represents comradeship in adversity, unflinching courage and self-sacrifice, then you are going to bristle when something bad is said about the nation. On the other hand, if Sparta symbolizes your dislike for those who systematically brutalize people who are weaker or younger, then any positive comments about Sparta are almost a betrayal. Taking hits from both sides probably means I got the balance about right. But it's rather like writing about Julius Caesar. Everyone has their own mental image of the man, and those who strongly identify with that image get irate with historians who upset it. |

| 2018-01-04 |

| Clio's companions |

| At a university, there's a distinction which makes me stand out from almost all other members of faculty. Unlike the botanists, the chemists, the gender studies people and all the rest I am a historian, so I have a Muse. That's not a 'muse' in the slightly patronizing way that creative types use to refer to the significant others in their lives - mine is an officially-credited, one hundred percent genuine, daughter-of-Zeus type of Muse. The type that 'museums' are named after. Meet Clio. She's the Muse of History. If you are wondering where the rest of the Muses are, mostly they are fighting for the attention of one solitary individual in the arts faculty. Budget cuts to the fine arts being what they are in a modern university, one rarely finds separate departments of Epic Poetry (supervised by Calliope) Elegiac poetry (Euterpe), Lyric Poetry (Erato) and Hymns (the appropriately named Polyhymnia). The Performing Arts take up most of the remaining Muses, with Melpomene (tragedy), Thalia (comedy) and Terpischore (dance). That leaves Urania, whom the astronomy faculty has to share with astrologers and (for some reason) lyre-tuners, though the latter probably do not keep her very busy these days. Of course the computing department also have a claim on Urania's son Linus, who is the mythological patron of computer nerds. So why does history have a Muse, and not, for example sculpture or painting? And why do writers of history books have this unfair advantage over biographers, travel writers and the writers of popular romances? The answer goes back to the Performing Arts which occupy so many of the other Muses. History was once also a performing art. History has a vital social function in that humans of all times and ages have wanted to know who they are and where they come from. Once Herodotus and other historians in the classical era would climb on to a podium and read aloud extracts of their work to meet that need. History was once related by the historian to a live audience. To keep that audience, the historian's material had to be both interesting and accessible to the general public. That's why historians have Clio - to help them compete with the poets and dancers and others who divert the public gaze. |

| 2017-12-04 |

| The Ghost of Christmas Past |

| Technically, it's still autumn until December 21st. It does not feel that way hereabouts, where the season of mists and mellow fruitfulness stopped being misty and fruitful around early November. Since then we have had just over six feet of snowfall, and temperatures last night scraped below -10c for the seventh or eight time this year. The fact that winter has come early and come hard is enthusiastically welcomed in town. Snowmobiles gambol (illegally) along the back streets en route to forest trails, where snowshoers and cross-country skiers have been having fun for weeks. The local ski resort is about to open, and all runs will be usable. Add shops packed with Xmas goodies and brightly-clad ski bunnies cluttering up the coffee shops, and there is a general feeling of celebration in the air. Yet it was not always so. For most of the history of the human race a brutal start to the winter was a cause for gloomy contemplation. That's when householders carefully checked their stocks of food and firewood, and calculated how much hay the livestock would get through, now that the snow had covered the fields. The idea that in future times people would anxiously hope for a 'good snow season' would have been incomprehensible to these folk. Snow was not just a nuisance, it was a killer that forced people and animals into shelter. And those shelters had better be stocked with resources to wait out the snow. As we prepare our platefuls of Xmas goodies, here's a thought - biscuits, jam, prunes, raisins, kippers, ham, bacon, sausages, cheese, and dozens of other foodstuffs were not created because they are delicious - though they are. These were all made from more perishable foods in the autumn and carefully packed away into the larder, designed to last and keep the household alive through the winter months. You didn't enjoy winter in antiquity - you hoped to survive it. |

page 1 page 2 page 3 page 4 page 5 page 6 page 7 page 8 page 9 page 10 page 11 page 12 page 13 page 14 page 15 page 16 page 17 page 18 page 19 page 20 page 21 page 22 page 23 page 24 page 25 page 26 page 27 page 28 page 29 page 30 page 31 page 32 page 33 page 34 page 35 page 36 page 37 page 38 page 39 page 40 page 41 page 42 page 43 page 44